Australian swans are black, while most swans are white. Why should this be?

When I was a child, growing up in Australia, the only swans I saw were black. At Lake Wendouree in Ballarat, or in the Botanic Gardens of Melbourne, the swans were slightly menacing in their quest for bits of bread, held out by my little-girl hand. All snakey black necks, gleaming red eyes and candy-red beaks, eager to peck and grab. I didn’t see my first real white swan until much later. Of course, all of the heroic swans in stories (e.g. The Ugly Duckling, Swan Lake) were white. Back then, most of our stories were still from the old country (Britain), and we were just emerging from the ‘white Australia policy’. Sadly, I don’t think we’ve fully escaped the latter, even today… but I digress.

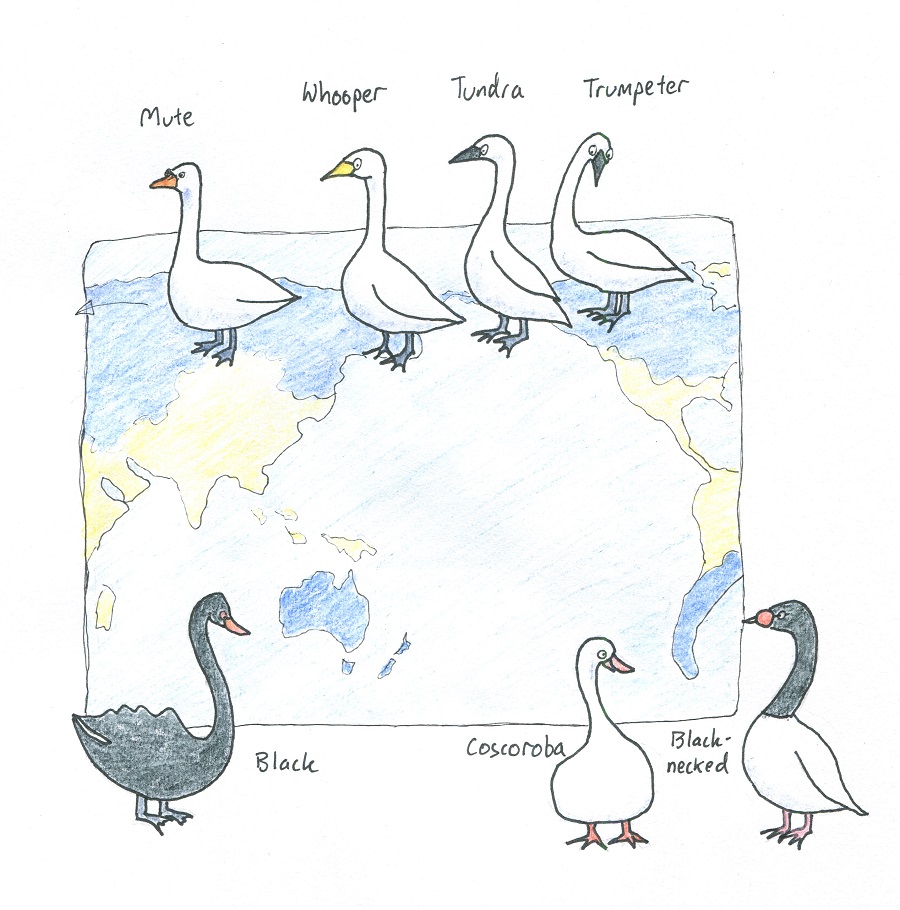

Globally, there are ‘seven swans a-swimming’: five species are white, one is white-with-a-black-neck, and one is black.

Before I go on, it’s important to remember that there doesn’t need to be an adaptive reason for everything in the living world. For example, armpits exist because of arms, not because having an armpit increases your chance of survival.* But it’s fun to speculate on the reasons for things, so here we go…

The colour of animals is influenced by:

1. the need to hide from, or deter, predators

2. the need to hide from prey

3. the need to look gorgeous to the opposite sex

4. other traits that may not be visible, but increase the chance of survival, and are genetically linked to colour.

Presumably, white swans can hide well in snowy or icy landscapes which are common in the northern hemisphere, and the southern end of South America, but are rare in Australia. The limited ice and snow in Australia might lessen the advantage of being white, and other colours might be better for camouflage. But why black and not some other colour? The Australian landscape is hardly black. But maybe our lake waters are darker because of higher levels of tannin. Or maybe the black swan evolved in a volcanic landscape with black lava fields and black-sand beaches (black swans are also found in New Zealand). But adult swans don’t have many predators. And black swans don’t need to hide from prey because they are vegetarian. For these reasons, I’m not convinced that swans are black because it provides good camouflage.

In animals, the colours brown, grey and black are created by the pigment melanin. This pigment also makes feathers stronger, and it’s thought that many birds have black wing-tips because high levels of melanin protect the flight feathers from wear-and-tear. But perhaps swans didn’t hear about this little secret because their flight feathers are white.

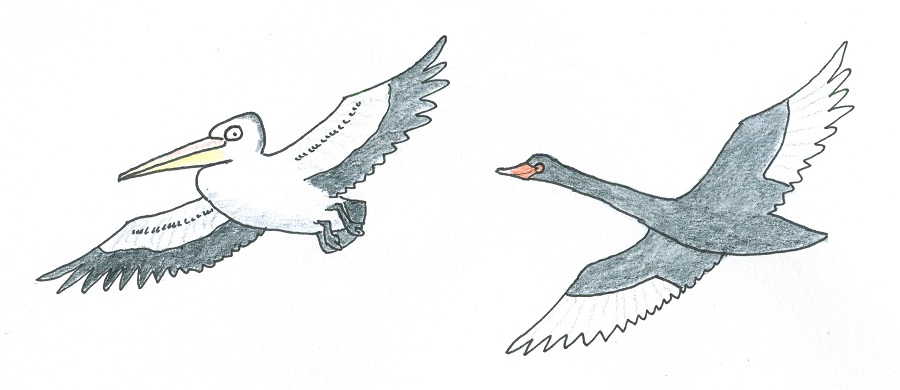

(A very realistic animation of a black swan flying can also be found here.)

Melanin also protects the skin against the damaging effects of UV radiation. I don’t know if similar protection is provided by melanin in feathers, and anyway, the skin of many swans (at least on their legs and feet) is already black.

Interestingly, some aspects of bird fitness have been correlated with the presence of melanin. Darker morphs of the tawny owl (i.e. those with more melanin) were found to have a better immune response than lighter morphs. Darker morphs of the screech owl appeared to be more stressed when exposed to cold temperatures than lighter morphs, experienced greater mortality in cold, dry winters, and were better at coping with warmer conditions. Could this also explain why the black swan is found in Australia, which has mild winters, and white swans occur where it is colder?

High levels of melanin have also been linked to reproductive success. Dark morphs of the feral pigeon were found to have larger testes and reproduced more often than blue pigeons. Perhaps the first dark swans to appear in Australian populations from chance mutation were carrying the same (hidden) advantages, and went on to dominate the gene pool until all Australian swans were black?

However, when animals choose a mate based on colour, this can also be influenced by the colour of their favourite foods. A bit like choosing a red-headed mate if you like to eat oranges, carrots and pumpkins. For example, female guppies prefer males with orange-spotted tails, and researchers reckon this is because they also like eating orange fruits. Interestingly, many birds prefer red and black to other colours. This may explain why many plants with bird-dispersed seeds package them up in red or black fruits, and why more bird poop ends up on red and black cars. So maybe the Australian swan ended up black with red eyes and a red beak simply because these colours were irresistible to the opposite sex?

Well after all that, I still don’t know why black swans are black. My brief, but fairly wide-ranging literature review has provided lots of ideas, but no definite answers. Even for our most familiar animals there’s still much we don’t know, and many theories that have never been tested.

Cockatoos are also either black (seven species) or white (11 species), with a few pink and grey ones (3 species) thrown in. Maybe they have some clues? But that’s another story, for another day.

* Also true for spandrels in cathedrals. For more explanation, see the classic paper: The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm.

Additional references:

Handbook of the Birds of the Word ALIVE

Hofreiter, Michael, and Torsten Schöneberg (2010) The genetic and evolutionary basis of colour variation in vertebrates. Cellular and molecular life sciences 67: 2591-2603.

Roulin, A. (2004). The evolution, maintenance and adaptive function of genetic colour polymorphism in birds. Biological Reviews 79: 815-848.

Hi Paula,

Well, this was a very interesting post and happened to come shortly after I’d been discussing this situation with northern hemisphere birding bloggers. I must send them links to your ideas and information. The fact that the colour of favourite foods may influence attraction to mating partners was something I hadn’t heard about. Thank you! It led to a humorous discussion about why one of my grown up children is possibly attracted to redheads! I was also interested to read about melanin strengthening feathers. The wonders of nature. Thanks again for a thought-provoking discussion, Paula.

Hey thanks Jane, I’d be interested to hear other perspectives on why our swans are black. As for mate choice being based on colour, let’s just say orange has always been my favorite colour 🙂

This post is really interesting Paula. I’ve always liked black swans. A couple of years ago we had a visitor from Norway and when I offered to show her black swans, she couldn’t believe there was such a thing. We have some on a suburban lake near Palm Beach so I drove her to see them. She was fascinated with them and watched them intently and took photo after photo. They were quite exotic to her yet I didn’t realise how novel they are. Now I can see how special they are.

I always enjoy your illustrations in your posts Paula. Thanks! 🙂

Hi Gail, thanks for reading and your encouraging comments. I enjoy noticing the unusual in the everyday. Cheers, Paula